Shared challenges

Building on the analysis of the digital maturity of the network, we are able to identify a number of shared challenges.

Many of the challenges we identified have reinforced the findings and relevance of the State of the Art, Chapter 2 of the Baseline Study. However, the digital maturity framework provides a different lens, and has surfaced other challenges specific to the network.

Given the range of digital maturity in the network, this section highlights challenges faced by a significant portion of the network, but not everyone. The intention is that those who have strengths in certain areas will share their experiences with others.

Insufficient foundations for digital transformation

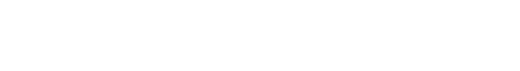

The majority of cities identified the need to build up internal digital capability. In many cities there was a lack of experience in digital development.

10/11 cities mentioned issues with data collection surrounding their chosen theme*

For many in the network, there was a limited understanding or confidence in data management, analysis, or ethics.

Many cities also highlighted the lack of infrastructure to enable their work, including limited connectivity or the lack of data centres.

6/11 cities said they have a digital transformation strategy*

Across the network, there was also a clear dissonance between the devices & tools available to civil servants within the local authority, and those in the broader territory, hindering the ability of the former to do their work effectively.

Traditional ways of working

Civil servants must often navigate complex gover ance structures and organisations that work in silos. Many cities noted the opportunity ASToN presented to ensure greater collaboration and coordination across organisations and teams. In some cases, ASToN also seemed to provide legitimacy to engage with the political level and with relevant national institutions and programmes (Ministries, National Agencies, Innovation Programmes).

Cities in the network largely operate in traditional ways, which is often limiting for innovation and adaptive practices. This includes very hierarchical structures within teams, limited empowerment of teams to take risks, and a focus on waterfall delivery (top-down hierarchical decision-making) rather than iterative development (through horizontal teams).

Even where cities have a mature and diverse local digital ecosystem, different speeds of working and traditional procurement practices limit the ability of local authorities to collaborate with technology companies, particularly startups. Where this collaboration exists, it is very often based on chance encounters and specific needs or a context within the local authority, rather than a collaborative process put in place.

Involving and understanding citizens

The continent has seen huge technological advances, including increased connectivity and usage of mobile phones, which can translate into new ways to interact with citizens. Nonetheless, these opportunities are balanced by a proportion of citizens that are illiterate, marginalised, or have limited access to digital technology due to cost.

Alongside this, many cities talked about the fact that citizens were reluctant to change their behaviour, or had traditional mental models. The readiness of citi- zens to use digital services can be a risk to the success of some projects.

All cities estimated that at least 60% of citizens own a mobile phone*

Authorities need a better understanding of their citizens, what they need and what motivates them, in order to make meaningful change. Central to this should be a commitment towards citizen involvement and participation in policy and service design, through approaches such as participatory policy making or user-centred design.

Only 4/11 cities use digital applications for citizens to make complaints or suggestions*

Local authorities also need to consider inclusion, to make sure they leave no-one behind with digital progress. For example, there are often few women on tech build teams, which are not representative of the populations they may serve.

The build or buy dilemma

Few local authorities have a full resourced in-house team. Even when an in-house team exists, the teams tend to be small and lacking vital skills. This means development cycles are long and slow-moving.

8/11 cities cited a lack of team resources*

Mechanisms for collaborating with the private technology ecosystem are varied, and co-creating solutions based on local need tends to be the exception rather than the rule.

Instead, local authorities opt for off-the-shelf solutions. These can have high maintenance costs, be difficult to sustain, and have limited flexibility to adapt based on feedback.

Many cities have a strong presence of a local digital ecosystem but the interface for collaborating with that ecosystem does not exist, and procurement practices do not allow for testing solutions with startups. Typically cities are buying off-the-shelf solutions from inter- national players.

It is important to emphasise that build and buy should be seen as equally appropriate options, depending on the nature of the problem being addressed, and the financial resources available. Even a fully resourced in-house team should always consider if a cheaper, off the shelf solution would be suitable before developing a new product and creating greater technical debt.

Furthermore, both build and buy require the local authority to have internal digital capability. Procurement of solutions from external suppliers still requires robust skills in managing these relationships.

COVID-19 outbreak

The cities in the network are affected by the outbreak of the coronavirus to varying degrees but all are feeling the impact of this global pandemic, both from a social and economic perspectives.

For many, the enforcement of social isolation has put into sharp focus the need to embrace digital and technology in order to remain connected and ensure that services can continue to be delivered to citizens.

Another aspect of the local governance that has been put under significant pressure during the time of the pandemic is local democracy through the ban of organizing consultations and meetings. Digitalization again can help fill the gap.

All cities must consider how this affects the work they are doing, how to mitigate its impact and to be adaptive to the changing situation.

Financial constraints

Digital and tech projects often involve high levels of investment in the early stages of the work, but there must also be investment in continued technical maintenance as well as service improvements.

For many the lack of funding could set a limit to their ambitions and was a source of significant concern. The cities must be ready to think creatively about how to source funding.

Sustainability

Across the board, the issue of environmental sustainability was not prioritised by the cities. This stands out as the global community continues to put this centre stage.

Sustainability of projects more broadly featured slightly more in discussions, but was often de-prioritised against other challenges. This lack of long-term thinking could pose a serious risk to the impact of the ASToN Local Action Plans unless cities consider this from the outset.

Theme choice

Across the network, cities struggled to commit to chosen themes with some changing theme at the last moment.

Many commented that while they had chosen to focus on something for the ASToN project, there would still be other work underway to address other problem areas. As such cities are keen to learn from the work one another are doing on adjacent themes.

Cities will need to have crystal clarity to focus their work, while understanding its place in the broader system.

Problem definition

Related to this, defining the actual problem to tackle within the chosen theme was challenging for the cities. Many wanted to focus on the solution and generating ideas, without a properly and very clearly-defined problem to design for.

This is a subset of the challenge of defining a theme, because even with a well-defined theme, in the complex system of a city and a city authority, it can be challenging to pinpoint one problem to focus on.

Work on this specific point will continue at the beginning of Phase 2 – Explore.

A note on self-reporting

Interestingly some of the data gathered in the questionnaire contradicted the insight gathered through other parts of our research.

9/11 cities claim to have their own website*

For example, many cities over-estimated their own capacity, while others claimed to have digital solutions and websites which we were later not always able to substantiate through our city visits.

The responses to these questions asking the cities in the network to assess their own capacity serve as an reminder of the importance of reflective practices, and the internal ability to monitor and evaluate. These skills are vital for digital transformation and well beyond that, they enable cities to assess their own starting point and make improvements.

*Data gathered from a questionnaire shared with all cities in Phase 1.