Testing through experiments

An experiment is a test we set up to learn something, with the aim to incrementally build certainty around the idea that you are developing. You should start experimenting with the most uncertain elements of your plans at a small scale, and increase the size and complexity of the experiments you undertake in line with that certainty.

This process of testing, learning and iterating should continue throughout the implementation of your plan so that you can continuously improve the service or product.

READ MORE:

• ASToN network, Experiments Catalogue

• Frontier Technology Hub, Thinking in Experiments

Identify your critical assumptions

Intentionally name the beliefs or assumptions you have about the idea you are developing and prioritise those that you need to test most urgently.

HOW:

- Bring together your Local Action Group to collectively surface as many assumptions as possible about the idea

- An assumption is a belief we have about the idea and how it’ll work. When we look at assumptions, we group them into four categories: People, Solution, Resources and Impact.

- Using your vision statement as the anchor for the conversation, ask your local action group to consider the following questions:

- People: Will citizens and stakeholders want it and engage with it?

- Solution: Is the solution feasible and does it work?

- Impact: Will the plan have its intended impact?

- Resources: Is the work financially and environmentally sustainable?

- Ask participants to write down the assumptions they are making within each category with sentences that start with “we believe…”

- “We believe people want this” isn’t going deep enough, ask yourself and the group ‘why’ we believe this and what needs to be true for the idea to work.

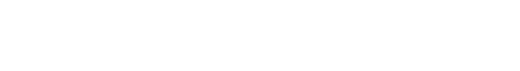

- Not all of these assumptions are equal. We’re more confident about some than others and, equally importantly, being wrong about some would be a bigger problem than others. The Critical assumptions are those we know the least about, which would also have the biggest negative impact on the idea we’re testing if proven to be false.

- Rank each of the assumption based on two questions:

- How much do you know about this idea? Or how much certainty do you have about it? This can range from: ‘I have a lot of evidence and no doubt that this is true’ to ‘I believe this but I am not sure at all’.

- How risky is this assumption to the idea? This can range from: ‘if this assumption is false, it would be impos- sible for this idea to work’ to ‘If this assumptions is false, it wouldn’t have any impact on whether the solution works’.

- Based on this ranking, build a list of the most critical assumptions: those that are least certain, and most risky.

EXAMPLES:

As part of the ASToN Network, the Niamey team identified the following critical assumptions within their plan to develop an online payment system for taxis.

- People: we believe taxi drivers have a mobile money account that they are familiar with using.

- Solution: we believe the tax collection platform can effectively collect and pay the taxes to the municipality.

- Resources: we believe that mobile money operators will be long-term partners to the city’s tax payment plan.

- Impact: we believe the tax collection platform will increase tax collection over time.

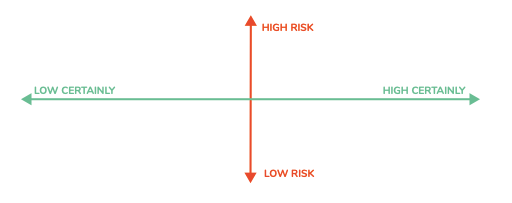

Design experiments

Design a series of experiments to test the most critical assumptions for your idea.

HOW:

- Start from your list of critical assumptions.

- Think through the following questions to design an experiment for each critical assumption;

- What are you testing? What is the specific assumption you’re looking to validate or invalidate?

- How will you test this? What is the specific and lean action you can take that will enable you to test the specific assumption?

- How will you prove it? What is the minimum, specific evidence you need to see to know whether the assump- tion is valid?

- Develop the experiment and exactly how you’ll deliver it in detail using the canvas.

EXAMPLE:

Niamey designed an experiment to address the assumption that the taxi and faba-faba drivers have a mobile money account that they are familiar with using. They designed an experiment where they would test the tax payment process and platform with a randomly selected group of 100 taxi- and 20 ‘faba-faba’ drivers.

They found that 60% of selected drivers already had a mobile money account, and 50% used it on a regular basis. However, drivers used a different mobile money provider than previously assumed. Of the pool of selected drivers, all were able to pay their tax through the platform. These findings were sufficient to validate using mobile money for the new online payment system.

READ MORE: ASToN network, Experiments Catalogue

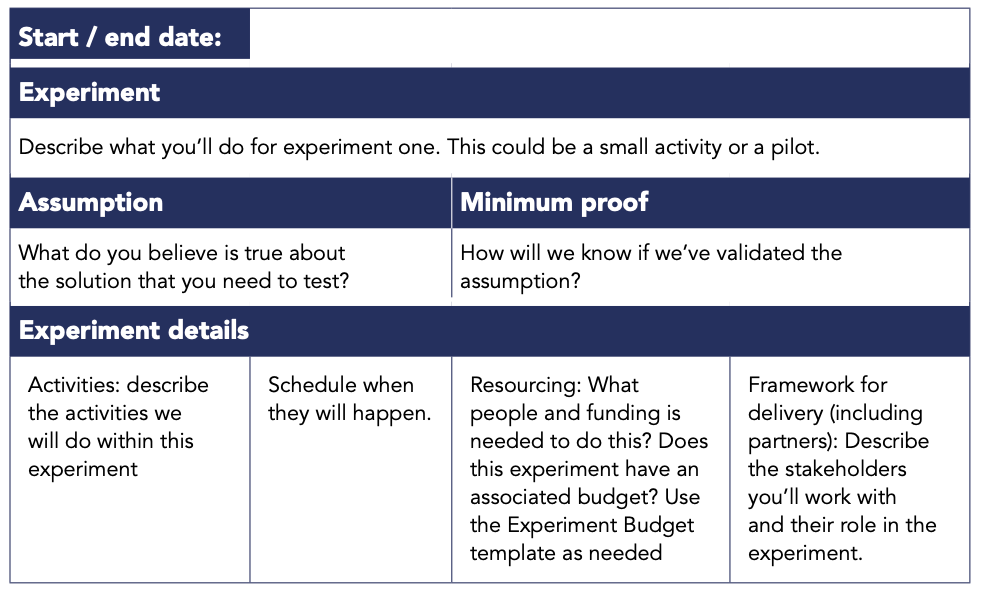

Managing and using data

Data and evidence are essential for guiding decision-making. The amount of data needed will vary at different stages of the work, with early stages typically characterised by testing early ideas through short sharp experiments, which require less robust data. Later on, you might consider more rigorous data collection mechanisms to inform your work on an ongoing basis.

HOW:

- Review your plan of action, which includes your planned experiments, and identify the evidence you need to collect around your vision, objectives, and experiments.

- For each of these pieces of evidence think about:

- What would you need to see, to know if you’re having impact/ achieving your vision?

- What data would show this? Note: not everything is measurable, and that insight from people is just as powerful. You need to find just enough, specific data to show you what you need to make decisions, in a way that enables you to iterate at pace.

- How can you collect that data? This includes data you might already have, such as national statistics, budgets, or numbers on service provision. Nationally collected data is not always reliable or centrally available. If this data is not easy to access, think about how you can collect data yourselves.

- What other insight or info might you want that’s not easily measurable?

- Note: when we talk about data, we mean a range of things, including: numbers, observations, stories, and facts.

EXAMPLE

Bizerte needed to understand whether the new solution they had developed was increasing the amount of waste collected over time. To do this, they observed and noted how much waste was collected on a weekly basis by a truck with the existing system. In the new solution, they embedded a way to collect this data. They then compared how much waste was collected in the existing systems with the new digital solution.

Learning and iterating the action plan

Learning and iterating is at the core of ensuring that you achieve your vision. As you build certainty about how your solutions work in the real world, you’ll need to reflect on your learnings and iterate how you plan to scale and sustain your idea over time.

HOW:

- We know that plans don’t go according to plan, which is why we embed experiments and data at the core of the action plans. It’s important to create space to learn and reflect on what the evidence is pointing to and what this means for the action plan.

- When you are designing your plan, decide on a rhythm for how you’re going to reflect. For example, this could be monthly or quarterly.

- During these sessions, go back to the evidence you have collected, and reflect on the following questions:

- What does the evidence tell us about the assumptions, objectives and vision we had?

- What have we learnt from implementation? What do we think needs to stay the same, and what needs to change?

- What elements of our action plan need to be adapted? This can be the idea itself, how it’s being implemented, the data we’re collecting, or the timelines we had assumed.

- Once you have reflected on this, embed these changes in your action plan.

- Repeat these sessions at the rhythm that you agreed at the start.

EXAMPLE:

By testing the tax platform with taxi drivers, the city of Niamey learnt that the mobile money platform used by most taxi drivers was different from the one previously anticipated. Therefore, the city pivoted to develop a partnership with a different mobile money operator.