Sèmè Podji, putting an end to the confusion over land ownership

This article is a collaboration between the Journalism and Media Lab (Jamlab), ASToN and Civic Tech Innovation Network (CTIN).

The Beninese city is in the process of digitising its land register. The change is in line with the land reform undertaken by the Beninese state to put an end to the challenges of traceability in land administration. “The pressure on land is such that people buy [land] unsuitable for construction.” Moise Chabi, a lecturer at the University of Abomey, emphasises this issue in his account of the spatial mutations that have taken place in Cotonou’s peripheral localities such as Sèmè Podji.

Located in the east of Cotonou, the population of this town in the province of Ouémé, in south-eastern Benin, has grown from 27,000 inhabitants in 1979 to 400,000 in 2020. Like in many African cities, inadequate laws, poorly kept land registers, corruption and fraud undermine land management, among many other problems. In Benin, 7,770 disputes were registered in 2016 in the different courts of the country, most of them in Cotonou with 20% of the cases on land ownership.

In order to tackle this challenge, Sèmè Podji joined ASToN, a network of 11 African cities developing leading and innovative digital projects to transform in an inclusive and sustainable way. This project aims to assist cities in their digital transition, through peer learning and sharing, over a period of 3 years between 2019 and 2022.

“We can say that the ASToN project comes at the right time in Sèmè Podji, and its implementation will allow us to solve the problems that undermine land administration,” according to Farid Salako, a local councillor and president of the permanent management committee for partnerships and projects of the Sèmè Podji local council.

The local ASToN coordinator, Landry Ahomadikpohou shares this sentiment. “For the time being, the meetings held with village chiefs, district chiefs, civil society and local councillors emphasise the need for this project, which will not only facilitate and give credibility to the work of the administration but can also serve the community.”

In terms of land management, Benin implemented urban land registers (RFU) from 1990 onwards to accompany a slow decentralisation process which became effective in 2003. A long period of administrative void during which “the institutional context did not favour the independence of project management and the accountability for the maintenance of the UFR tool, which resulted in the failure of the systems put in place”, states a UN-Habitat report on Beninese urban land registers and municipal ownership of land information.

In her thesis on Beninese land registers, Claire Simonneau, a doctoral student in planning at the University of Montreal, points out that during this process, “the publication of land and property information was not without reluctance: most towns inherited photocopied documents that could not be used, while the sub-prefectures kept the originals of the subdivision and reclassification registers”.

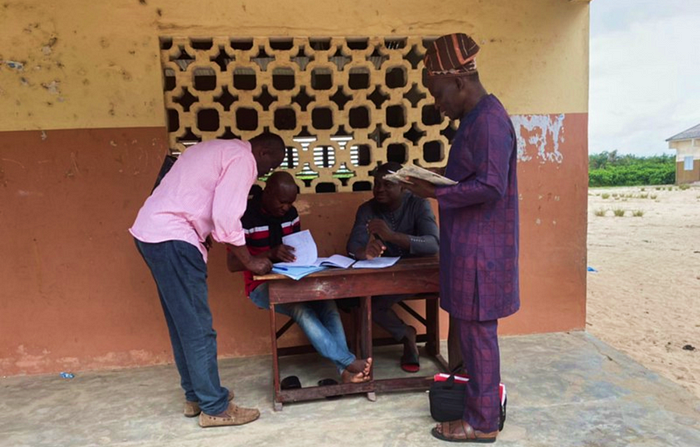

Sèmè Podji currently has a paper-based land register that does not cover all six districts. This affects the land management, and the issuing of land titles is slow.

According to the local ASToN coordinator, the disadvantages of the current system are twofold. One is related to “actions leading to fraudulent transactions”, which are a source of land conflicts, and the other is inherent in the “issuing, by the administration itself, of deeds on the same property to different presumed owners”, explains Ahomadikpohou.

Since 2013, a large-scale reform project has been undertaken by the Beninese state. One of the key points is the introduction of a new single land ownership document: the Titre Foncier or title deed. According to the National Agency for Land and Property (ANDF), there are only 40,000 land titles issued to date. This upheaval in land administration by the state seems to be leading to a general movement in the country.

“The land reforms undertaken in Benin force the regional administrations to be in full control of their land management system,” according to Salako.

Following the 2013 reform, the national digital land registry was established to allow the full record of the “land at local or national level, and all related information”.

The local coordinator of ASToN notes that since 2016, the ANDF has implemented several land policies, strategies, and programmes.”Sèmè Podji is one of the ten towns involved in the land administration modernisation project which takes into account the districts of Sèmè Podji, Agblangandan and part of Ekpè,” according to him. Salako emphasised that the towns chosen for the pilot phase will ensure that reliable digital land information is available to the central government,” in addition to responding to a local priority, because “today, the need for this system is pressing,” he adds.

The city is currently in the engagement phase of their ASToN project. Thir aims are to gather all the relevant stakeholders and to work around the challenges of land management from a data perspective, and also to start designing together a digital tool that can help them ass the situation on the ground according to Landry Ahomadikpohou. “In the long term, we expect to see fluidity and transparency in land administration through the digital management of this data,” according to the local coordinator., He also notes that the project has broad aims because “it is not just a tool for the city, but something that serves both the local and national levels”.

For more information on the 11 ASToN cities, visit www.aston-network.org.

Written by Moussa Ngom.